Customs and Etiquette of the Shikoku Pilgrimage

Temple Etiquette for Pilgrims

To experience the Shikoku pilgrimage at its fullest, it’s a good idea to visit temples as more than a tourist. One can participate in time-tested rituals which, when done, show reverence and respect. Remember: while Japanese temples are used for many things in their communities, they are primarily a sacred place for people to go and pray. It is also good to know what to do at temples... after all, there are 88 of them (and if you count bekkaku, even more).

All temple offices along the Shikoku Pilgrimage route are open from 7am to 5pm, every day of the year. At 5:01pm, stamp offices (“nōkyōjo,” 納経所) close their doors to the public, but temple grounds will remain open for a while longer. Therefore, if you are running out of time and arrive just before 5pm, you can first rush to get your stamp before performing rituals and enjoying the scenery.

Entering a Temple

(1) Make sure you check the posted signage before entering a temple. Many have rather strict rules around photography and videography, especially when photographing statues or deities. At busier temples, photographers can clog paths and disrupt the peace.

(2) As you approach the “sanmon” (山門), or main gate into temple grounds, bow slightly. Take off your hat (unless you are wearing the pilgrim sedge hat).

(3) Ensure that you step over and not on the threshold between the outside and temple grounds (“kehanashi”, 蹴放し). This often looks like a raised wooden beam that runs the length of the main gate. The threshold is highly symbolic and represents the very hospitality of the temple itself; to step on it is disrespectful. Keep an eye out for more kehanashi within the temple grounds.

Within a Temple

(4) Purify your hands at the hand-washing station (“temizuya”, 手水舎), usually located near the entrance of the temple, by following these steps:

- Pick up the ladle (“hishaku”, 柄杓) with your right hand, fill it with water from the basin (“chōzubachi”, 手水鉢). Step back a bit so that “dirty” water does not fall back into the basin, and pour about half over your left hand

- Transfer the ladle to your left hand, and rinse your right hand

- (Optional) Fill the ladle with water once more and cup one hand. Pour some water into your cupped hand before bringing it to your mouth. Rinse your mouth and spit it out onto the ground or grates where people do not stand

- Lastly, pour out the remaining water in the ladle onto the ground or grates before returning it to its original spot

- Some temples provide towels on the side to dry your hands

(5) Head over to the bell tower (“shōrō”, 鐘楼) and gently ring the bell once using the attached rope. Do not ring the bell as you leave the temple; this is considered very bad luck.

(6) Bring your copy of the Heart Sutra, spare change, a name slip (“osamefuda”, 納め札) (optional), two candles (optional), and six incense sticks (optional) to the main hall (“hondō”, 本堂). Here you can choose to burn candles and incense as a form of prayer and offering. If you choose to do so, you should light one candle and three incense sticks in each the main hall and Daishi Hall. Many pilgrims (Japanese and foreign alike) skip the candle and incense parts of visiting a temple.

Steps for visiting a Shikoku temple’s main hall:

- Place your walking stick into a container located next to the steps of the hall

- Use the large starter candle provided by the temple to light your candle. Do not use other people’s candles to light your own - this can signify inheriting their bad luck or sins. Once lit, place it in the candle box (“rōsokutate”, 蝋燭立て)

- Light three incense sticks with a lighter and place them in the middle of the incense burner (“kōro”, 香炉), or as close to the middle as possible if it is crowded. The most common interpretation of incense is that each stick represents an offering to the past, present, and future Buddha

- Whether you are leaving just a name slip or a hand-copied sutra, place them in their corresponding containers. The container for name slips is called “nōsatsubako” (納札箱), and the container for hand-copied sutras is called “shakyōbako” (写経箱).

- From a close distance, gently throw about ¥5-¥25 yen into the big box in front of the hall. If you’d like to give more, put into the monetary offertory box (“saisenbako”, 賽銭箱) in front of the deity statue. The statue is located behind the front doors of the hall

- If there is a bell above the monetary offertory box and you made a donation, gently ring it once

- After giving a donation, clap your hands together (“gashō”, 合掌) and begin chanting the Heart Sutra. You should start from the first page of the Heart Sutra; read from right to left, then flip to the other side and continue from right to left again. The following gathas should be chanted three times: “hatsunodaishingon” (発菩提心真言), “sanmayakaishingon” (三昧耶戒真言), “gohonzongoshingon” (御本尊御真言), “kōmyōshingon” (光明真言), and “kōsokōbōdaishigohōgō” (高祖弘法大師御宝号).

(7) Perform the exact same ritual at the “Daishidō” (大師堂). The main hall faces the entrance of the temple, and the Daishi Hall is typically somewhere off to the side of it.

Finishing Up

(8) Now that you’ve completed your temple rites, it’s time for a very special souvenir! Head over to the stamp office to receive a stamp (“nōkyō”, 納経).

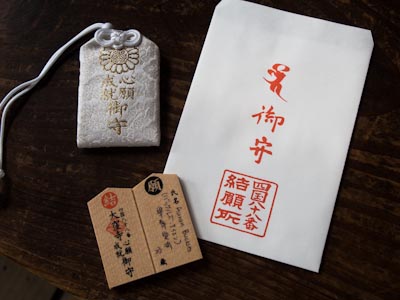

(9) Don’t forget to collect your “miei” (御影), or an image slip of the deity, at that temple. You will find them somewhere on the counter in the stamp office. This is included in the price you paid for the stamp. One can also ask for a “mieibukuro” (御影袋), which is just a small paper bag, to hold all their miei (or buy a miei collection book, called a “mieichō”, 御影帳). At the stamp office, you can also shop for other goodies, like good luck charms (“omamori”, お守り), pictured below.

The year I first went on the pilgrimage was the 1,200-year anniversary of the pilgrimage, so they had special colorful miei slips. But the ordinary ones are beautiful too (in black and white).

(10) As you exit the temple, turn around and slightly bow toward the sanmon gate. You’re finished!

Calligraphy Stamps

At each temple, a pilgrim may purchase a calligraphy stamp at the stamp office (“nōkyōjo,” 納経所). These are comprised of handwritten characters (“sumigaki”, 墨書き) and 2 red stamps (“shuin”, 朱印), and are placed in their stamp book (“nōkyōchō”, 納経帳). Getting a stamp typically costs between ¥200 - ¥500 yen. Pilgrims can collect stamps at bekkaku temples as well. If you run out of pages, kindly ask the temple staff and they will sew on a few more for free.

The practice of writing stamps originated from a policy called “tochi kinbaku” (土地緊縛) in the Edo period (1603-1868), which regulated and restricted the movements of ordinary people. Pilgrims were required to obtain travel permits and follow main paths; thus, the nōkyōchō served as a proof of passage.

Osamefuda Name Slips

Most pilgrims carry paper “osamefuda” (納め札) name slips, said to derive from the legend of Emon Saburō. Pilgrims leave osamefuda in each temple and give them to those who have gifted them osettai. Similar to the stamps, osumefuda serve as proof that one has visited the temple. It is said that when Emon was chasing after Kūkai, because he would miss him by just a little at every stop, he nailed his name slips on the walls inside temple grounds so that Kūkai might see them when he came back around.

Shikoku’s Osettai Culture

In Shikoku, there is a tradition of respect for pilgrims, who are called “o-henro-san” (お遍路さん). If you appear to be on pilgrimage, people may treat you with courtesy or go out of their way to guide you to your destination. Groups of children may greet you formally or offer well wishes, and others may give you small tokens or favors called “osettai” (お接待). Osettai culture is a beautiful part of what makes Shikoku special.

Osettai can come in the form of fruit, meals, car rides (although you can politely reject this if you are solely walking), or even money. Pictured above are some osettai goodies offered by an unknown stranger, found at a rest hut along the trail.

In exchange for osettai, a recipient pilgrim should always, if possible, give the gifter an osamefuda. This is a good way to express gratitude, especially if you do not speak Japanese. Never ask for or expect osettai. Gifts are given by the goodwill of the locals.

Staying Polite

Many know Japan’s legendary reputation as an orderly society that enjoys making and following customs. To truly immerse oneself while on a pilgrimage, one should try to follow the local ways of life. Some things that are considered normal in your own country might be perceived as rude in Japan.

- Take your shoes off before entering any tatami room or a professional establishment (like a clinic or hospital). If you see a “step up” or cubbies near the entrance, that is usually a sign to take off your shoes

- Reservation cancellations - especially to minshuku or ryokan - should be avoided as they can cost an innkeeper dearly. Japanese people rarely cancel

- As the pilgrimage grows in popularity, be aware of the evolving local opinion around sleeping outside

- Take-away containers (“taking out”) at restaurants are not common. In Japanese culture, one is expected to order only what they or their companions can reasonably eat

- Except for dietary restrictions, order modifications at restaurants are often not allowed in Japan. The idea is that one should enjoy the food in the way the chef intended it

Consider reading Don Weiss’s excellent essay on “The Heart of a Henro”.

Other Pilgrimage Traditions

- When walking over a bridge, try not to touch your pilgrim staff (“kongōtsue”, 金剛杖) to the ground. Legend has it that Kūkai may be sleeping underneath

- When you stay at acommodations in Shikoku, leave your pilgrim staff in the genkan, or “shoe area,” of the room. There will sometimes be a holder for this purpose

- Similarly, you will often find a spigot or bucket of clean water near the entrances to pilgrim lodgings. These are provided for henro to wash the ends of their walking sticks

- It used to be a tradition to receive calligraphy stamps on one’s white pilgrim vest (“hakui”, 白衣). If you do not plan to wear the vest, this is fine. If you do plan to wear it, you should get the stamp in your stampbook instead